Unsolicited Career Advice

Goals and Scope of This Post

This post is for students entering or currently enrolled in liberal arts programs at four-year degree granting colleges in the US (though hopefully it’s helpful for others as well!). The goal of this post is to discuss how to best spend your four years in order to be able to build a successful career afterward. This post focuses specifically on how to build a successful career, but of course there are other important reasons to get a liberal arts education and attend college, such as becoming a better human being and citizen, learning how to be independent, having fun and being in community.

The definition of a successful career is deeply personal, and depends on your personal values, desire for impact, desired life style, and more. But as Cal Newport argues in So Good They Can’t Ignore You, having control over your career is the “dream-job elixir,” so this post will focus on how to build skills that you can leverage to gain control in your future career.

Early Career Archetypes

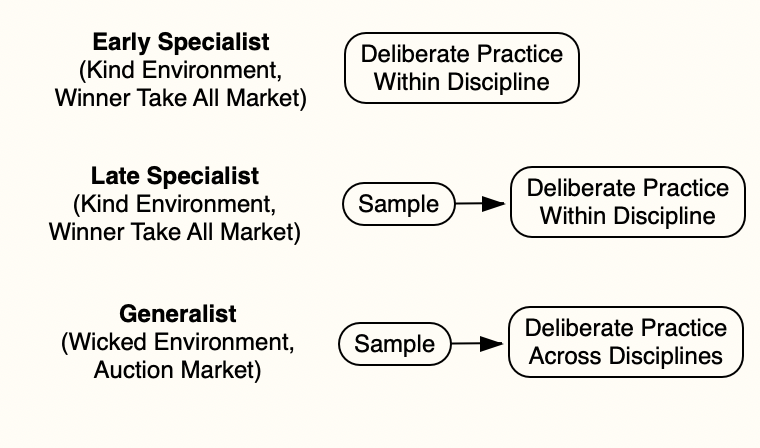

If building skills gives one leverage to gain control in their career, college is an important place for many people to start building those skills. There are a few different paths to skill building that depend on what sort of discipline(s) you decide you want to build your career in. Let’s assume there are three main archetypes that people are likely to fall into early in their careers: early specialist, late specialist, and generalist:

Which path makes sense for you depends on the kind of learning environment of your pursuit (kind vs. wicked), the type of market your pursuit is in (winner take all vs. auction), and when you choose to specialize (“early” vs. “late”).1 Let’s define these terms quickly before diving in further.

Learning Environments

Kind and wicked learning environments are distinguished based on the feedback they provide and the “rules of the game.” Kind learning environments are characterized by frequent and helpful feedback and consistent rules (chess, classical music). Meanwhile, wicked learning environments have infrequent or inconsistent feedback and changing rules: you don’t consistently know whether you made the “right” decision or not (if there is even a “right” one at all), and the rules of the game are always evolving (research, jazz). In a kind learning environment, you learn the most from practicing within that environment. Meanwhile in a wicked learning environment, you learn the most from experimentation and working across disciplines.

Career Markets

Career markets are about how skills are leveraged for control, and line up well with kind vs. wicked learning environments. A winner take all market involves mastery of a specific skill or set of skills that everyone is working to execute. To get an edge, it’s best to focus specifically on that set of skills. Meanwhile, in an auction market, the way you differentiate yourself is through your unique set of skills, and people aren’t trying to be exactly the same, so you benefit from focusing on your unique strengths.

Early vs. Late Specialization

Finally there is early vs. late specialization. This is about when you specialize and whether you spend time “sampling” different disciplines or not. Most people who specialize early are people who know from a young age that they have talent in and want to pursue a specific field, such as elite athletes, chess players, and classical musicians. If you’re attending a liberal arts college, you probably are not an early specialist; an early specialist would benefit most from specific study in their discipline even from a young age.

Sampling and the Liberal Arts

So, if you know you are likely to be a late specialist or a generalist if you are attending a liberal arts school, how do you figure out which one you are and go from there? The answer in both cases is what’s called “sampling,” and it’s a key feature of a liberal arts education, which focuses on breadth and broad training over highly specialized training. Even though most liberal arts schools require you to choose a major(s), your typical liberal arts engineering major, for example, will be less specialized than an engineering major graduating from a technical school. The key to a successful liberal arts education is leveraging this breadth rather than having it hold you back.

Making The Most Of Sampling

The breadth of a liberal arts education is most impactful if that breadth is used to 1) figure out what you might want to study further and 2) build skills that can be applied across disciplines. A liberal arts education allows you to explore rather than being locked in to a specific discipline by your twenties, and allows you to develop skills that will be helpful no matter what you go on to study next. When you sample a discipline, be intentional about learning what the key questions and methods of that discipline are, what it might be like to work in that discipline, and what skills you can build to get further in that discipline and/or apply to other disciplines. Sampling is beneficial regardless of whether you go on to pursue a specific discipline thereafter, or choose to pursue a more interdisciplinary career.

As you begin to home in on what you might be interested in (which may or may not be before you even graduate!), you can begin to consider if you’re interested in disciplines with profiles suited to late specialization or a generalist approach. A late specialist should focus on identifying and building important skills in a discipline as soon as they’re sure that is what they want to pursue. Meanwhile, a generalist should focus on adaptability and a broad range of skills; for these kinds of disciplines it’s beneficial to continue to study broadly, and leverage skills you’ve learned from different domains while sampling.

The Costs of Early Specialization

Although most people who attend a liberal arts school are not what I referred to as “early specialists,” there is still a lot of pressure to specialize in fields that have a higher earning potential out of the bat, like STEM fields or finance. This is especially an issue in today’s economy where people go into debt to attend school, or who need or want to make more money to take care of themselves and their families. Additionally, if you don’t know what you want to do, you might be tempted to apply to graduate school to put off making your decision. Getting a high paying job out of the bat or pursuing an advanced degree seem like clear investments, and will probably pay off in the short term. But it’s important to consider the potential risk of early specialization along with its benefits. If you specialize too early and something about your situation changes, those skills developed for your first discipline may not be worth as much as they were originally. This could be due to external factors, like changes in the market, but it could also be due to your own internal preferences, like realizing a discipline isn’t working for you. Even if you want to specialize in undergraduate, at a liberal arts school you ultimately won’t be able to specialize all that much, so it is best to focus on foundational skills, even if you narrow down to focusing on a specific discipline/major. This gives you an opportunity to set yourself up for the future and experiment in a lower stakes environment than having to repeat this process after college.

Focusing on Deliberate Practice

Once there has been enough time for sampling and you feel that there are specific disciplines or types of disciplines that you’d like to consider further, it’s important to begin building skills in those areas by deliberate practice. Deliberate practice is a term that comes up a lot when talking about specific types of learning in kind environments, and involves tight learning cycles, feedback, and even coaches to improve. Here when I refer to deliberate practice I mean intentional skill building, even if feedback isn’t clear (such as in wicked learning environments).

In college, it typically makes sense to focus on building skills that you can use to get your first opportunity after college, regardless of whether that’s full time employment, further education or starting your own venture. This will require you to research the discipline(s) you are interested in and see what skills are valued by employers/schools/the marketplace. Then make a plan to build some of those skills to make yourself a worthwhile candidate. For example, let’s say you know you want to study biomedical engineering. Spend some time researching different paths people take: do they get advanced degrees? Go straight into industry? What skills do they have that you might need to build? Common ways to build skills include taking relevant courses, doing a directed reading, focusing on a topic in a final project or term paper, getting an internship or research position, taking relevant standardized testing, etc.

What To Do If You Don’t Know What To Do

When you are early in your career, you are still figuring out what disciplines interest you and building up skills in and across disciplines. If you’re legitimately not sure what you want to do next, even if you’re about to graduate, that’s totally fine! In this case, continue focusing on exploring, and think about what value you have to offer others.

Sometimes it isn’t clear exactly what path to take after sampling. Is a late specialist model or a generalist model a better fit? One thing to consider is what kinds of environments you thrive in. Do you want to be great at a very specific thing, better than everyone else? You might want to consider specializing. Or do you want to express yourself creatively and find your own niche? You might want to consider a more generalist path.

Applying For Your First Opportunity Post Undergrad

When applying for your first opportunities after college, it’s important to focus on skill building and what you might offer others, rather than worrying too much about what you might ultimately want to do. Many students who get liberal arts degrees are deeply interested in social justice or entrepreneurship, which is awesome! But, to have an impact in the world, you need the right skills, resources and knowledge to innovate. Focus first on building up valuable skills and expertise that you can use to identify and tackle problems that resonate with you. The right mission will come to you when it’s time, you’ll build traction, and you’ll know you’re on the right track.

When it’s time to apply for your first opportunity post college, it’s important to discuss the breadth of your experience as a strength, including how your path thus far has shaped your experience and what you bring to your future position. Apply for opportunities where you’ll be supported and have a chance to develop additional skills. Don’t worry if the first opportunity you have out of college isn’t everything you’ve dreamed of - by investing in fundamental skills now, you’ll unlock more opportunities in your future.

Conclusion

A liberal arts education affords a breadth that is a real strength: helping you figure out what career paths to pursue and building rare and valuable skills that you can use to lead an ultimately fulfilling career. By focusing on exploring your interests and then deliberately practicing in your target discipline(s), you can gain control over your career and your life.

Further Reading

This post only scratches the surface on thinking through how to create a successful career for yourself. Here’s some further reading that inspired me to write this post:

- So Good They Can’t Ignore You by Cal Newport

- Range by David Epstein

- Saving The Liberal Arts by David Perrell

And here’s a few articles about “playing the long game” in the liberal arts:

- To see how liberal arts grads really fare, report examines long-term data

- In the Salary Race, Engineers Sprint but English Majors Endure

- The world’s most creative people have one thing in common

Footnotes

-

For the sake of this piece I am assuming that there are only two combinations of learning environments and markets: kind/winner take all, and wicked/auction market. ↩